As the title is hinting, this is part one of a series of entries to follow. This first post will deal with a topic that I personally have to touch on a lot: Deploying to Cloud Run. Why? This very blog you’re reading right now is deployed precisely that way. In this article, we’re going to walk through a couple of simple steps to get a hugo based blog (or anything more or less) deployed to Google Cloud Run using GitHub Actions.

Prerequisites

You don’t need a lot, except a GitHub repository and a Google Cloud Platform account.If you don’t have one, you can create an account for free and get 300$ free credit, which will serve you for a pretty decent amount of time. We will get into the cost of this a bit further down the line so that you can get a good overview of how much bang for your buck you will be getting. One other thing that may be good is an idea of what to put in your blog, but essentially the whole deployment mechanism will work regardless of that.

Hugo

Hugo is describing itself as “The world’s fastest framework for building websites.”

I would say it is a neat tool to help you build static websites very fast and easily. I found it particularly useful for creating pages that host documentation or a blog.

Depending on your host system, there are various ways available on how to install it, if you don’t want to build it from source, which you, of course, could do relatively quickly, as it is all golang based. I’m on a Mac, so for me, the install process is as easy as

$ brew install hugo

and I’m ready.

Creating the blog

Now that we have all our prerequisites ready, we can start to create our blog. Start by cloning your GitHub repository to your local machine.

$ git clone [email protected]:RiRa12621/blog.git

Cloning into 'blog'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 59, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (59/59), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (45/45), done.

remote: Total 59 (delta 13), reused 41 (delta 5), pack-reused 0

Receiving objects: 100% (59/59), 15.97 KiB | 3.19 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (13/13), done.

$ cd blog

Presumably, you are sitting in front of an empty repository by now and are ready to go.

$ hugo new site . --force

Congratulations! Your new Hugo site is created in /Users/rrackow/blog/.

Just a few more steps and you're ready to go:

1. Download a theme into the same-named folder.

Choose a theme from https://themes.gohugo.io/ or

create your own with the "hugo new theme <THEMENAME>" command.

2. Perhaps you want to add some content. You can add single files

with "hugo new <SECTIONNAME>/<FILENAME>.<FORMAT>".

3. Start the built-in live server via "hugo server".

Visit https://gohugo.io/ for quickstart guide and full documentation.

You may be wondering, “why are we using --force” and I would too. The new site command tells hugo to create all files to bootstrap a new static website.

It then requires a path on where to create said files. You can now give it an

arbitrary name, but since all that is going to live in this repository, in our

case, is the blog, we may as well put everything in the top-level folder, and

that is what . is doing. The --force option is required since the top-level

folder isn’t empty as the .git folder already exists here. If we tried without

the --force flag, we’d get the following error:

$ hugo new site .

Error: /Users/rrackow/blog already exists and is not empty. See --force.

Now that we got our initial bootstrapping done let’s add some nicer layout to it. A set of layouts is available on https://themes.gohugo.io/, and they’re all being installed the same way. So in the following example, I am adding the “Ananke” theme.

$ git submodule add https://github.com/theNewDynamic/gohugo-theme-ananke.git themes/ananke

Cloning into '/Users/rrackow/blog/themes/ananke'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 2125, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (145/145), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (103/103), done.

remote: Total 2125 (delta 54), reused 101 (delta 33), pack-reused 1980

Receiving objects: 100% (2125/2125), 4.44 MiB | 9.76 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (1151/1151), done.

What’s missing? Some content! So we’re going to add a new post like

$ hugo new posts/my_first_post.md

/Users/rrackow/blog/content/posts/my_first_post.md created

$ cat content/posts/my_first_post.md

---

title: "My_first_post"

date: 2021-10-11T16:32:46+02:00

draft: true

---

The hugo new <path/to/file.md> command creates a new file with the required

header for the later generation of the static pages.

There’s a critical remark here: draft: true is the default, however by default

, hugo doesn’t generate static pages for draft pages, so make sure to set it to

false once you’re happy with your post.

Use your favorite editor to add all the essential things you want to tell the world to your first post like

$ echo "Lorem Ipsum" >> content/posts/my_first_post.md

At this point, we are done with the initial content creation and can move right on to the deployment.

Since we’re reasonably happy with our content, we can go ahead and check it in.

$ git add .

$ git commit -m 'bootstrap files and initial content'

$ git push

Package it up

Next up is to create a Dockerfile that we can then build an image from to deploy

. While we could have left it in the top-level folder, I opted to create an

extra deploy folder, just in case we would like some different configuration

or need additional files.

mkdir deploy is all that is required to do so.

Now we can take a look at what to put in our Dockerfile. While we could run a hugo web server in the container, I preferred to use a more established tool that works great for the job: Nginx.

Use your favorite editor again to create a Dockerfile in the deploy folder

similar to the following:

FROM nginx:alpine

COPY public_html /usr/share/nginx/html

# Make sure we listen on a port but also accept variables

COPY nginx.conf /etc/nginx/conf.d/configfile.template

ENV PORT 8080

ENV HOST 0.0.0.0

RUN sh -c "envsubst '\$PORT' < /etc/nginx/conf.d/configfile.template > /etc/nginx/conf.d/default.conf"

EXPOSE 8080

CMD ["nginx", "-g", "daemon off;"]

Let’s talk about what is happening here so you don’t just blindly copy and paste.

We start from an alpine-based image with Nginx installed, then copy over

/usr/share/nginx/html to public_html.

(Don’t worry about this part too much, as we will cover it in a tiny bit when we

talk about the GitHub actions.) Next, we define two environment variables,

PORT and HOST. Nginx will pick those up after we inject the PORT value

into its config two lines later. Of course, we could set them right away in the

final line, but Cloud Run needs to be able to modify those, which is possible if

they’re environment variables. Now we set a default port to expose, namely 8080.

This value can be overridden when launching the container later on. Finally, the

CMD to start up Nginx in the foreground inside the container.

Deploy to Cloud Run

All of the above was quite a lot of preparation before we got into the core of what we wanted to achieve; however, the whole thing wouldn’t work without something to deploy.

Google Cloud

We said that we needed something to deploy, but definitely also need something to deploy to. As mentioned in the prerequisites, you should have a Google Cloud Platform account already. Now you need to perform a set of steps. The Google Cloud documentation is more complete than this blog could ever be, so each of the steps will link to the documentation’s corresponding parts. Google has improved the documentation, and now most sections contain instructions on how to perform the required steps from the UI or the CLI.

-

Add the following Cloud IAM role to your service account:

-

Cloud Run Admin- allows for the creation of new Cloud Run services -

Service Account User- required to deploy to Cloud Run as service account -

Storage Admin- allow push to Google Container Registry

-

-

Add the following secrets to your repository’s secrets:

-

GCP_PROJECT: Google Cloud project ID -

GCP_SA_KEY: the downloaded service account key

-

Action

Before we move ahead, let us quickly map out what is about to happen next: we are going to create a GitHub action that creates the static files to add to our container image, later on, trigger a Cloud Build, so our container image is readily available in Cloud Run and finally deploy to Cloud Run. This sounds like a lot, but you’ll see that it is not all that complicated after all.

First, we must create a folder that houses all things related to GitHub specific

behavior, like sponsorship for your repo and actions, so logically GitHub

requires this to be called .github. Now inside here, we need another folder

called workflows, which will be the home for all actions in this repository.

We end up with a structure like below:

.

├── FUNDING.yml

└── workflows

└── cloudrun.yaml

This can be extended by adding more actions, each in its separate file.

Time to fill cloudrun.yaml with the instructions for what our action is

supposed to do. We will break this down into smaller chunks and look at the

whole file at the end. You can scroll all the way to the bottom if you are just

interested in the entire file.

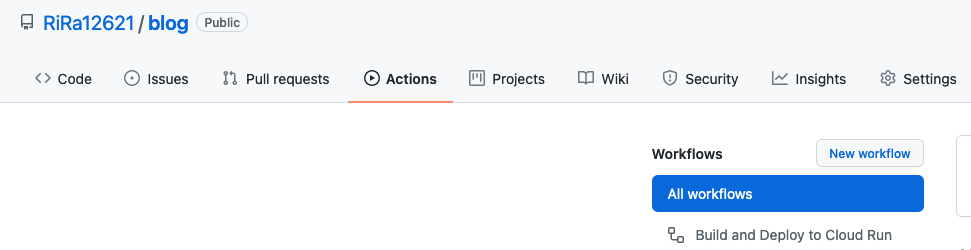

name: Build and Deploy to Cloud Run

on:

push:

branches:

- master

This is the beginning of our file. name: defines the name that will be shown

under the “actions” tab on GitHub.

The next bit is defining when the action should run. In our case, we would like to run on every push to the master branch. Note that if you do not define the branch, this action will run if you push something to a feature branch, which can be impractical if you write a new post on a different branch as part of your workflow.

Let’s move to the next section:

env:

PROJECT_ID: ${{ secrets.RUN_PROJECT }}

RUN_REGION: us-central1

SERVICE_NAME: rackow-io-blog

This part sets up any environment variables for the whole action. As you can see

with the PROJECT_ID, you can reference GitHub secrets. We went over how to get

those values and add them as GitHub secrets in this post’s

Google Cloud section. Additionally, you have to set a region

and a service name, which you can freely choose.

Here is the complete list

of currently available Google Cloud regions.

jobs:

setup-build-deploy:

name: Setup, Build, and Deploy

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

Next is setting up the actual jobs. Since we have all in one job for this, I named it appropriately and then picked a machine type to run on from the the list. This machine will be used for all of this job, so that is for the complete action in our scenario.

steps:

- name: Checkout

uses: actions/checkout@v2

with:

submodules: true

Now we get into defining the actual steps. Each uses a pre-defined action and

some parameters with it. The first thing should always be checkout so that the

repo gets checked. We have to add the submodules as well, as our theme is a

submodule.

- name: Setup Hugo

uses: peaceiris/actions-hugo@v2

with:

hugo-version: '0.69.0'

- name: Build Content with Hugo

run: hugo -t lekh --minify -d deploy/public_html

The above steps set up hugo and then run the command to create the static

files. Finally, those files are placed into the deploy/public_html directory.

# Setup gcloud CLI

- uses: google-github-actions/setup-gcloud@master

with:

version: '286.0.0'

service_account_email: ${{ secrets.RUN_SA_EMAIL }}

service_account_key: ${{ secrets.RUN_SA_KEY }}

project_id: ${{ secrets.RUN_PROJECT }}

This basically sets up gcloud to be used inside the action with the

information you added earlier into your GitHub secrets and specifies a version

to use rather than defaulting to master.

Now last but not least, we’re getting to building and deploying:

# Build and push image to Google Container Registry

- name: Build Image

run: |-

cd deploy && \

gcloud builds submit \

--quiet \

--tag "gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/$SERVICE_NAME:$GITHUB_SHA"

# Deploy image to Cloud Run

- name: Deploy

run: |-

gcloud run deploy "$SERVICE_NAME" \

--quiet \

--region "$RUN_REGION" \

--image "gcr.io/$PROJECT_ID/$SERVICE_NAME:$GITHUB_SHA" \

--platform "managed" \

--allow-unauthenticated

Those two steps are leveraging gcloud that we set up in the step before to

trigger a Cloud Build and then deploy the respective image via Cloud Run.

Now add all the files, commit and push.

$ git add .

$ git commit -m 'my first action'

$ git push

That’s it. You should see your new blog deployed if you browse to the Cloud Run dashboard.

There are some exciting things that you can do from here on, like monitoring your service or mapping it to a domain that you own. So feel free to let me know if you’re interested in that and if it should be covered in one of the following posts.

Until then…